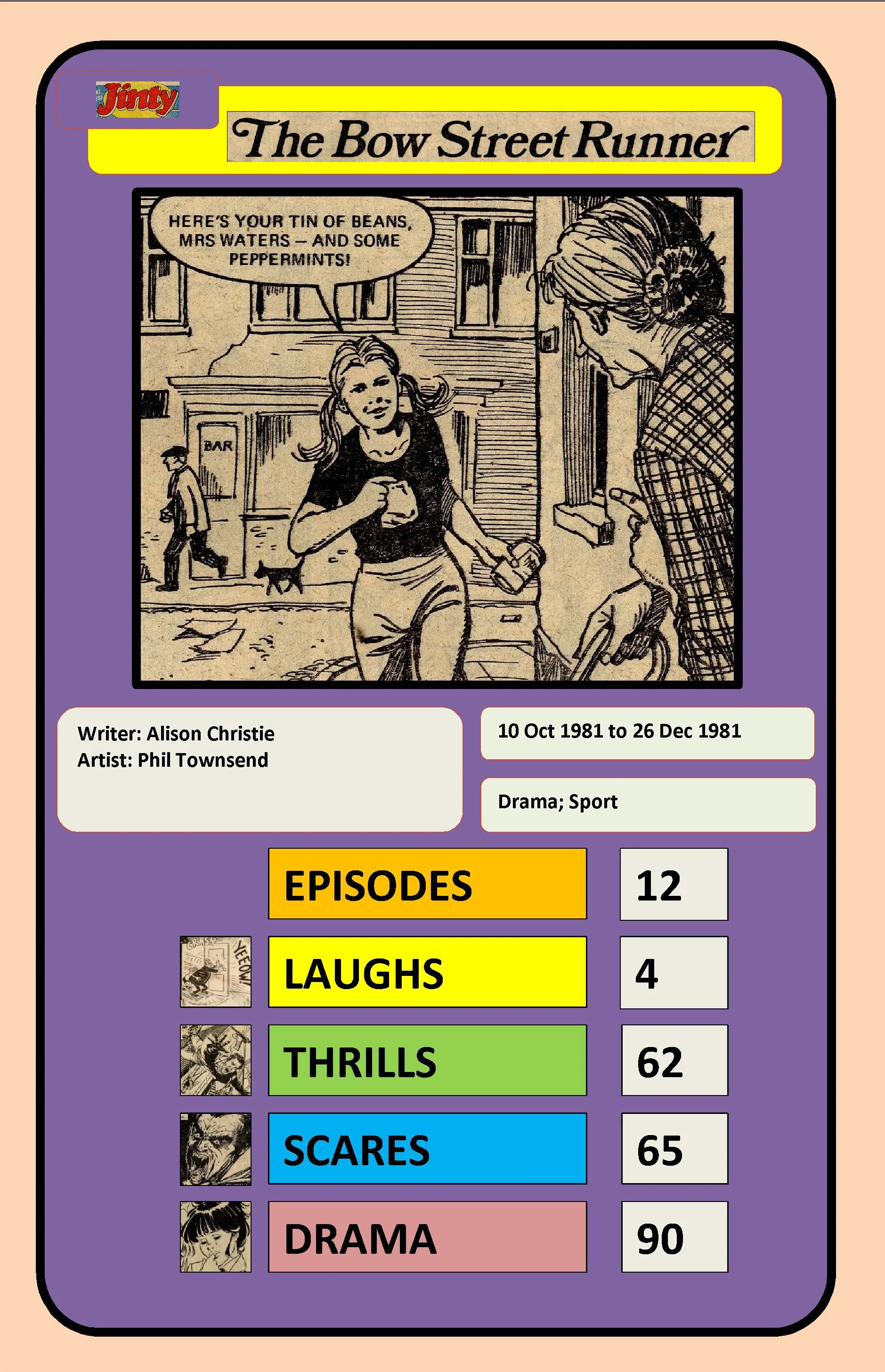

Story File: The Bow Street Runner

This twelve-part story, written by Alison Christie and drawn by Phil Townsend, combines a certain poignancy – of having been published across the end of the excellent Jinty’s seven-year run and the first few issues of the newly-merged Tammy and Jinty – with a disturbing commentary on the pressures facing traditional British communities in the harsh, free-market, social upheavals of the early 1980s.

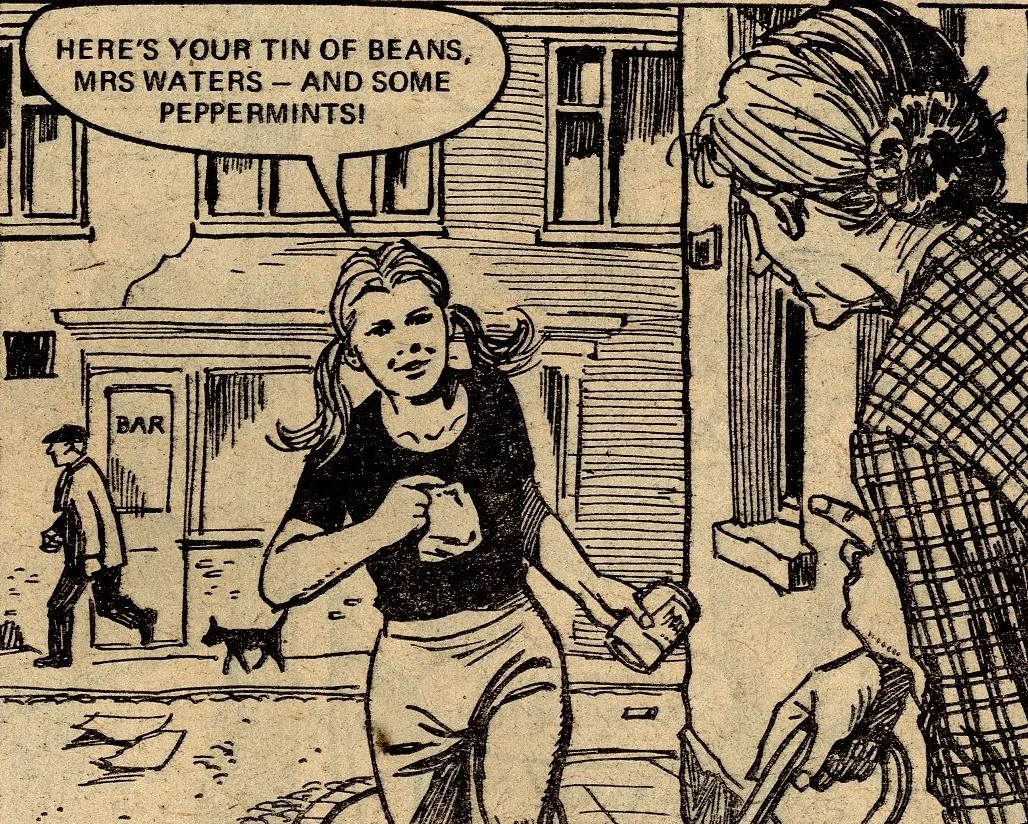

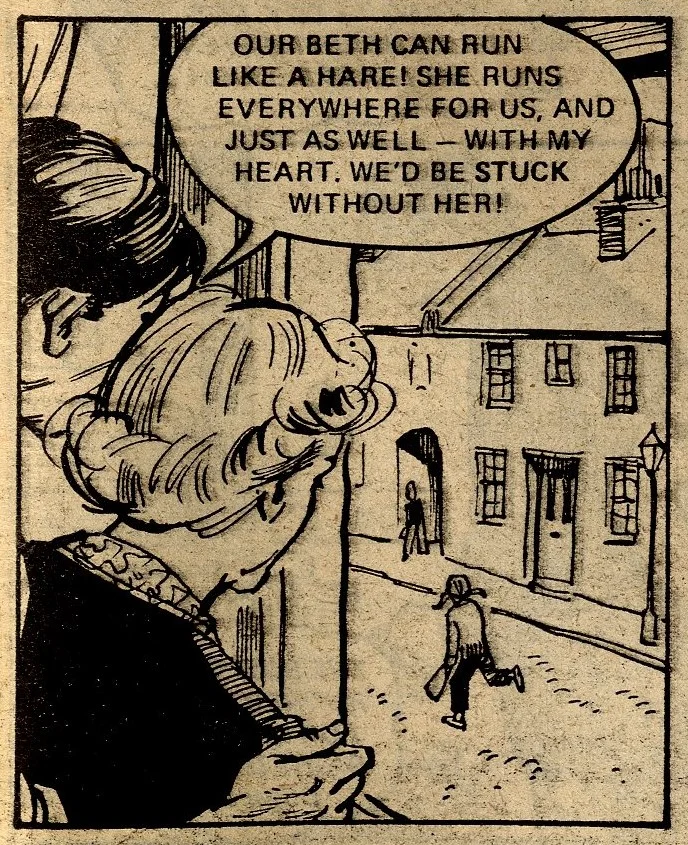

The Bow Street Runner is Beth Speede, the single child of parents who are both in poor health (Dad has a debilitating heart condition, and Mum is described vaguely as both ‘lame’ and ‘crippled’), and resident of Bow Street, a poor residential neighbourhood in an unnamed town or city. Beth loves to run, and has been literally running essential errands – collecting shopping and doctor’s prescriptions – for as long as she can remember. Most of the time she does so with a smile, but in private, the responsibilities weighed heavily on her young shoulders: ‘The Bow Street folk are too hard-up to have phones – and most of them are either old, or have young families! They depend on me!’

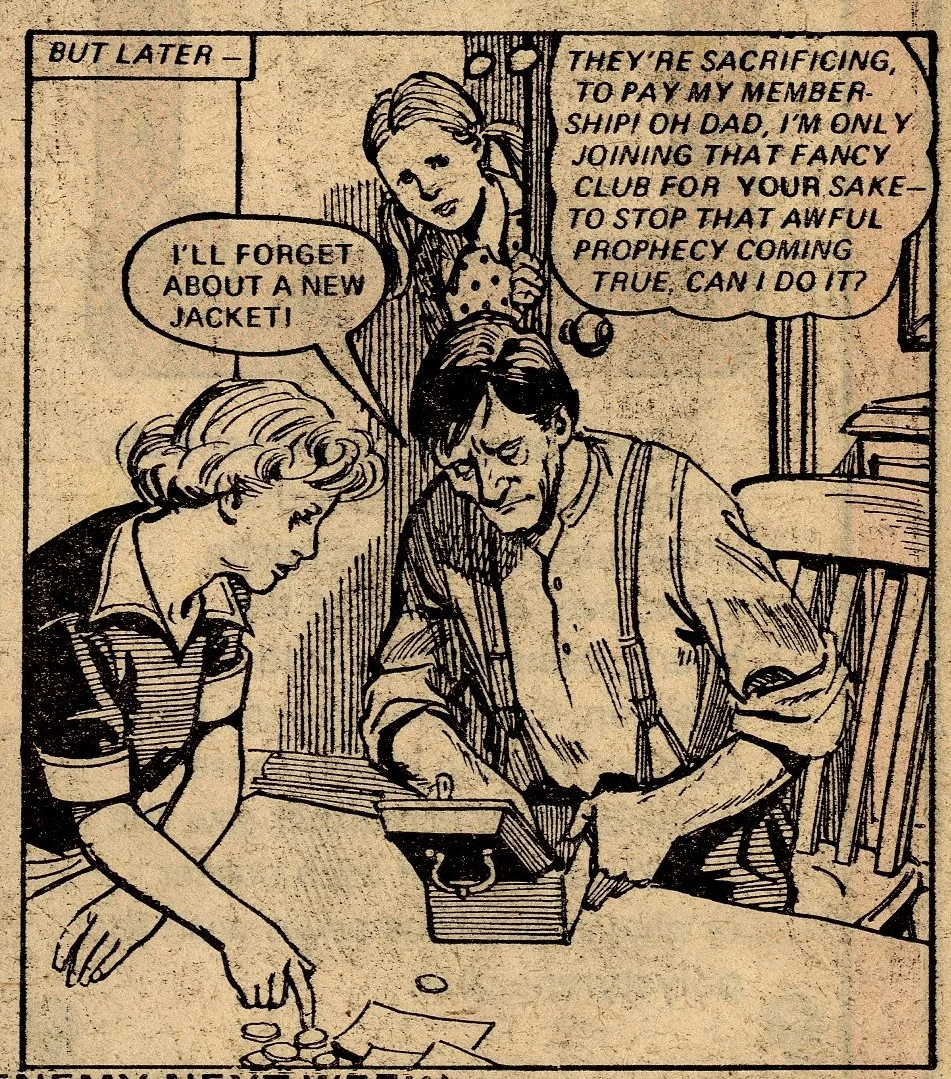

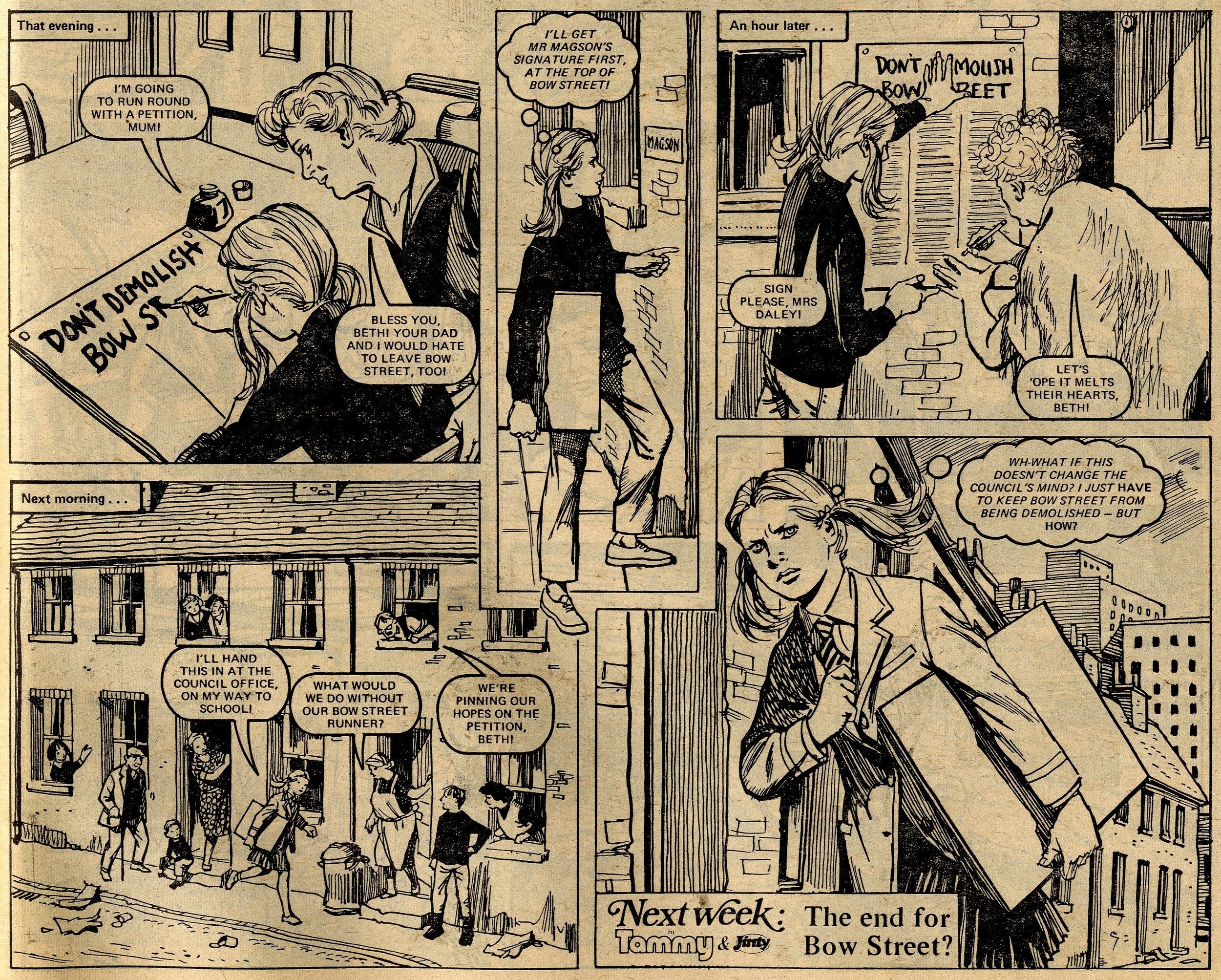

A fairground fortune-teller – a familiar narrative device in girls’ comic tales – foretells a scenario in which Beth was running across green fields, and a girl was crying. Beth interprets this as a prediction of her father suffering a heart attack and her running across fields in an unsuccessful attempt to get help. In order to train herself for this eventuality, she joins an out-of-town cross-country running club, but is entered for a race which leads to a friend of the family offering the Speedes use of their cottage in the countryside. All of a sudden, Beth’s interpretation of the prophecy changes – now she believes that her father’s heart attack will occur while he is in the remote cottage and it will become even harder for him to receive help.

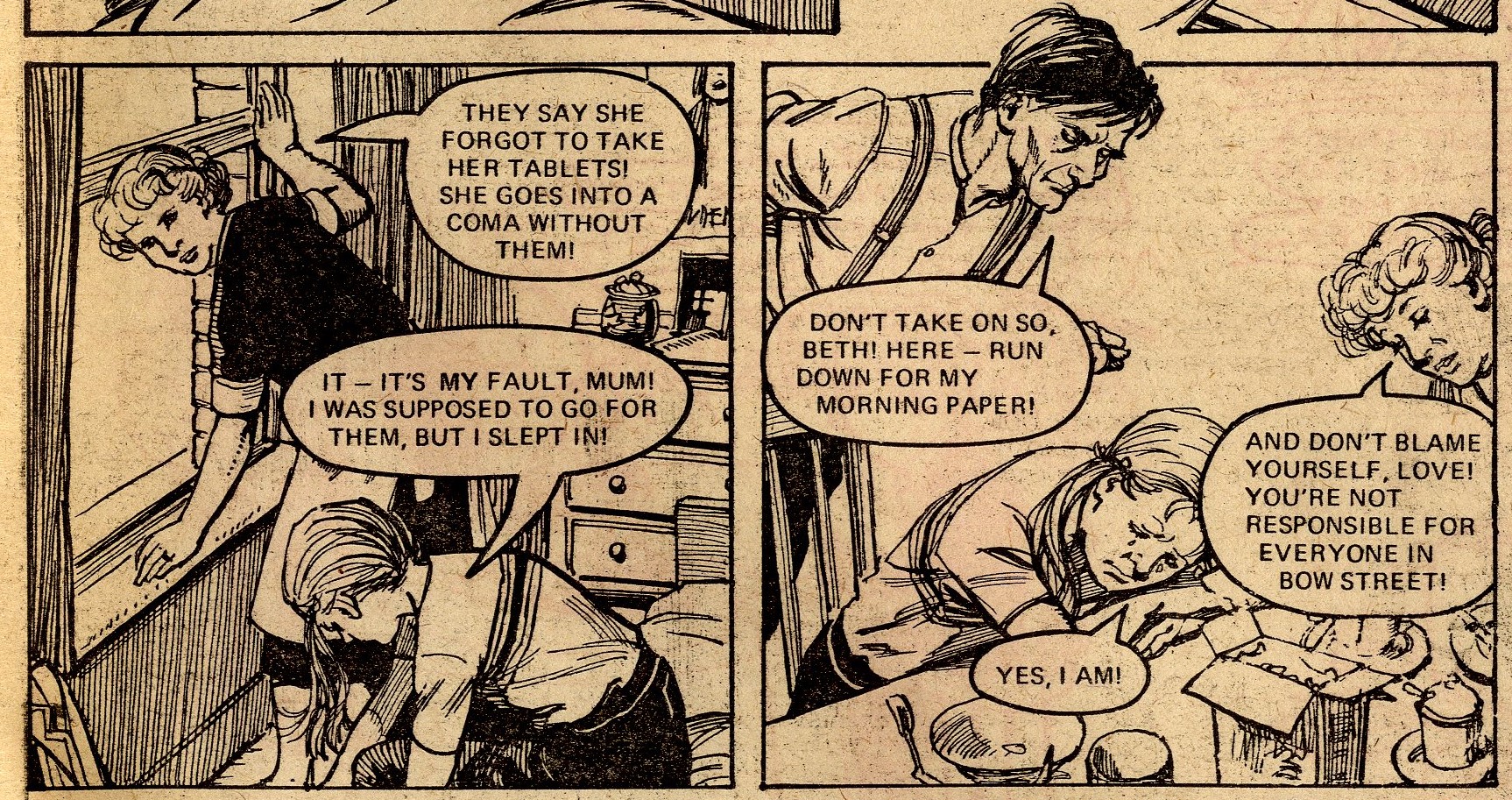

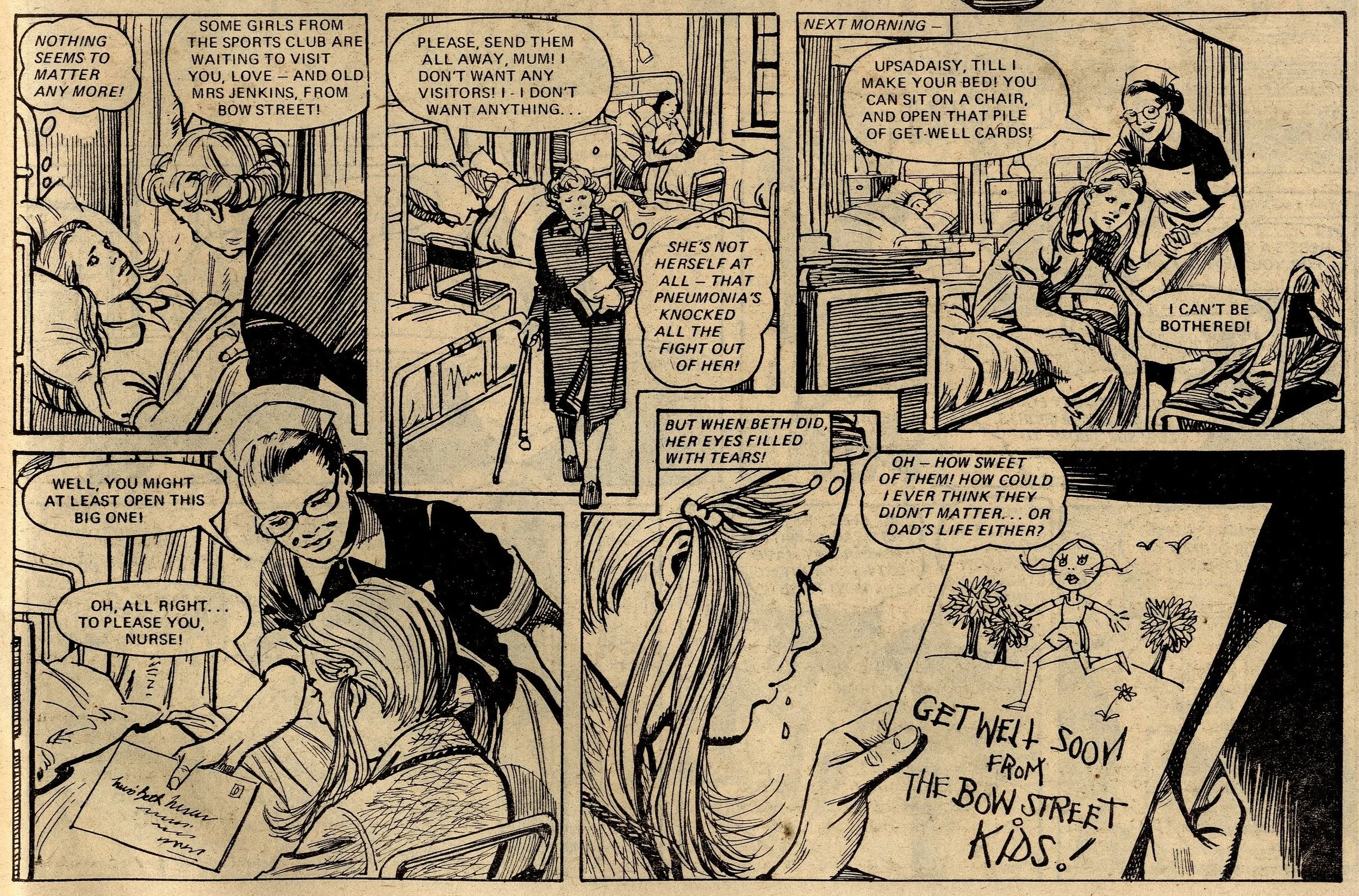

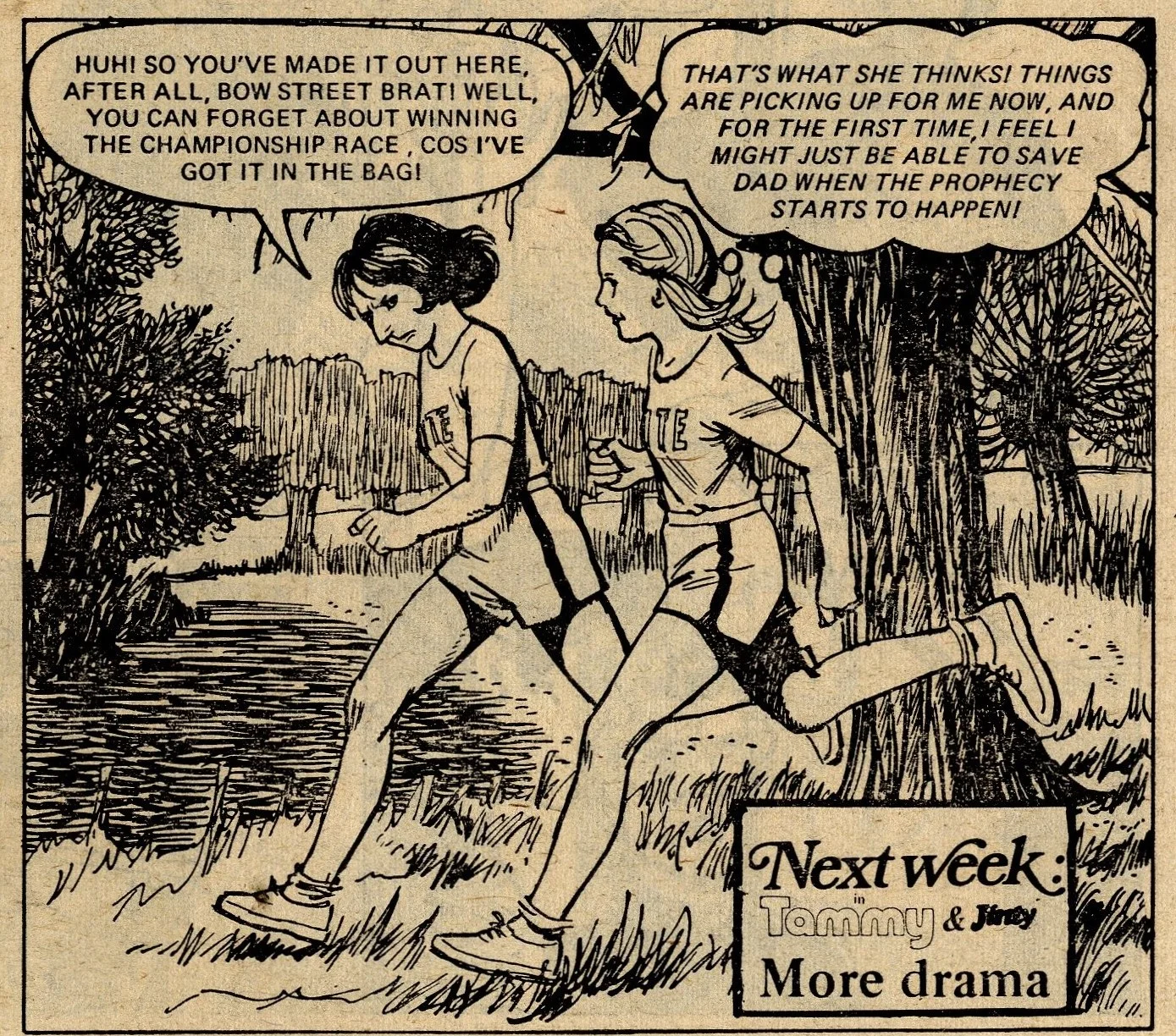

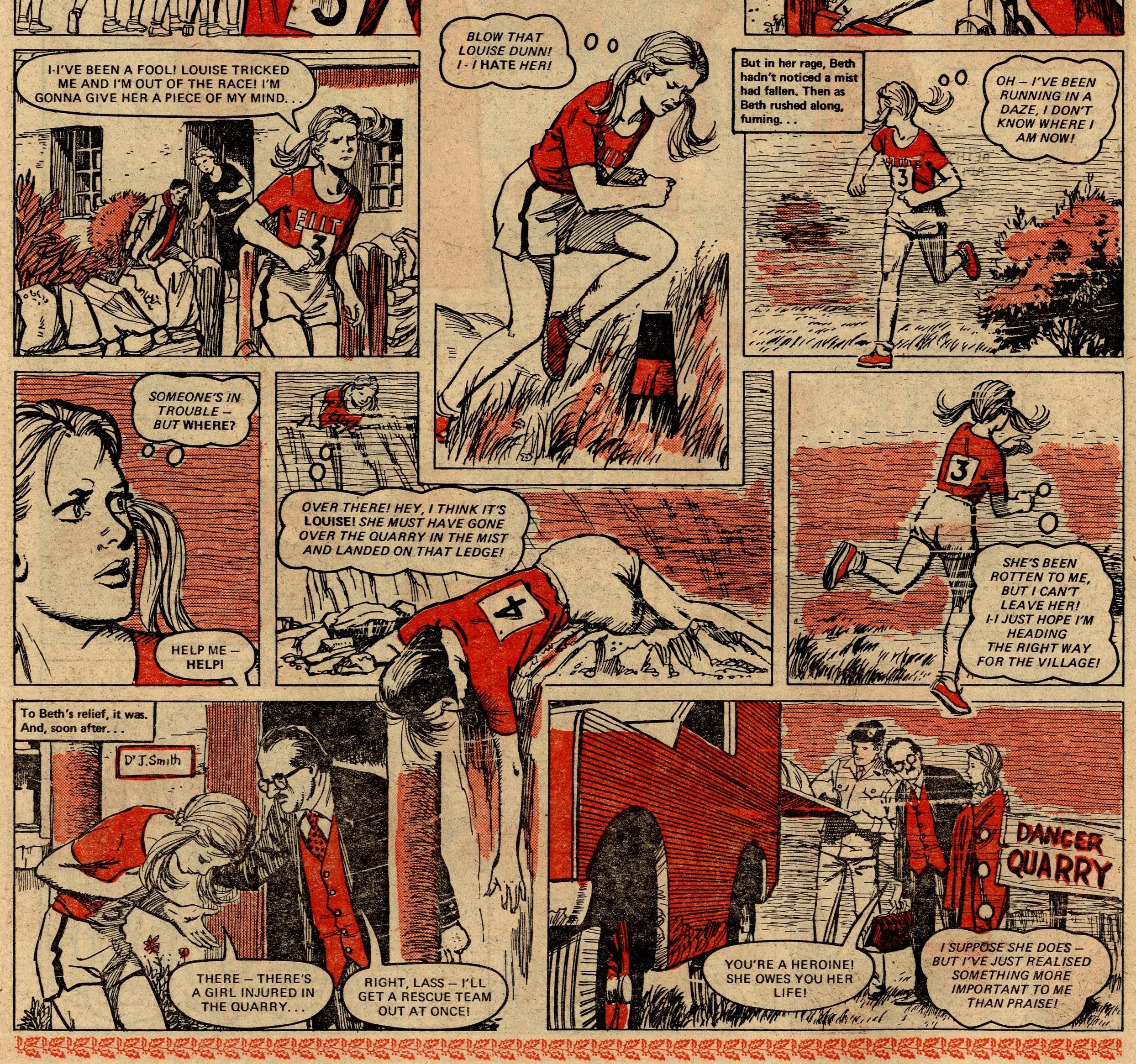

To make matters worse, Beth has a rival at the cross-country club – stuck-up Louise Dunn, who tries to exploit Beth’s kind heart at every opportunity to wreck her chances of winning the competition. Exhausted by Louise’s machinations, and increased pressures in support of her needy neighbours, Beth suffers a breakdown, contracts pneumonia and loses both faith in herself and hope in life. One feels led to ask why one so young was placed under such enormous pressure, and where was the support from the State – but, of course, there was none available. Would there be today? Probably not. Beth’s parents don’t come out if this particularly well either – there’s the distinct impression of taking her for granted (at one point, Mum tells her ‘That’s what a daughter’s for – helping her mum and dad!’) until she breaks down.

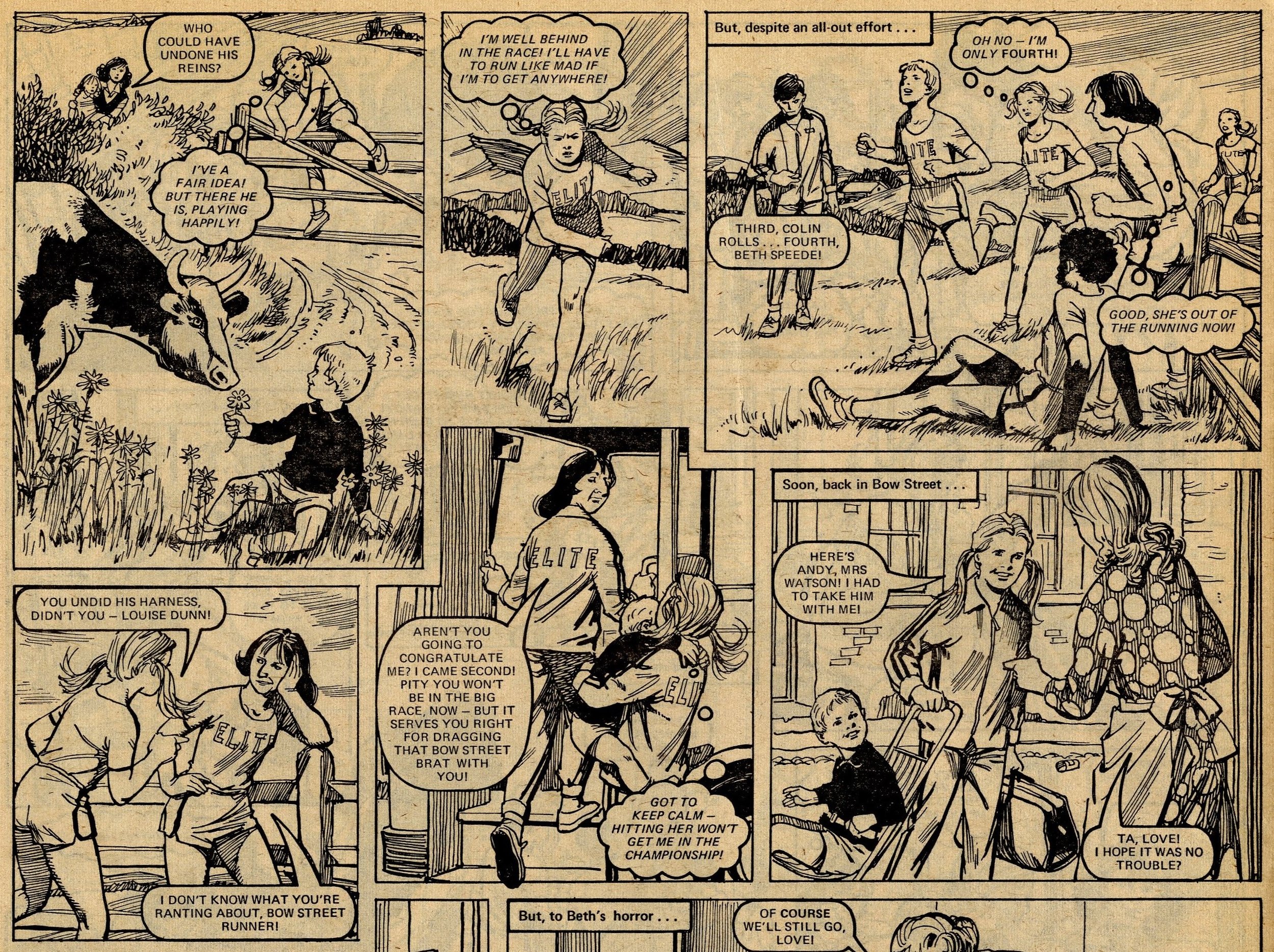

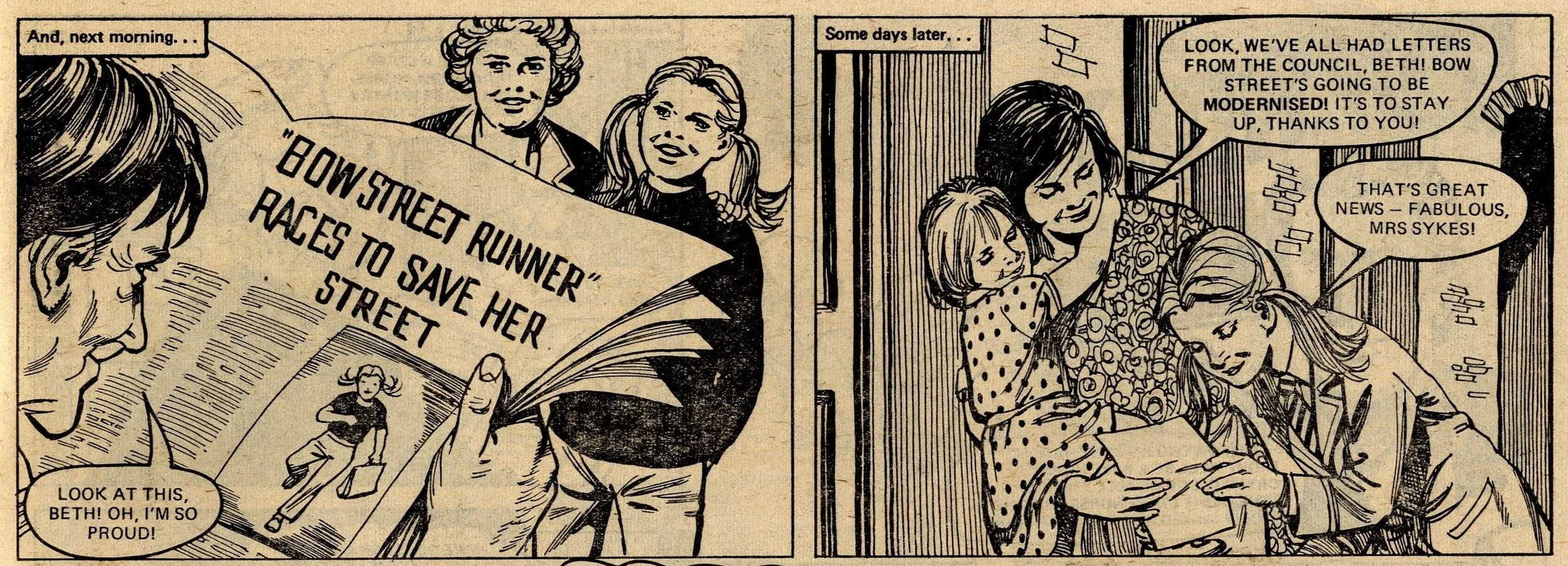

The stakes grow higher when all the residents of Bow Street receive a letter from the council announcing that the street has been scheduled for demolition – to be replaced by modern but community-lite flats built by Louise’s property developer father. But Beth’s fightback begins when the local newspaper runs a story on her plight and the new development is cancelled. In the big race, she rescues Louise who has fallen down a quarry in thick mist. The race is re-run, Beth wins and, as a reward, Louise’s dad builds the Speede family a special bungalow at the top of Bow Street which enables Beth to continue running errands for her neighbours … which pleases Beth, but I wonder whether it was really what she needed. Still, the social order was maintained and consciences were no doubt salved. Let’s try not think about the state of Beth Speede’s physical, mental and emotional health today.