Hatch, match and dispatch!

'GREAT NEWS INSIDE FOR ALL READERS!!' 'Two great papers join forces!' 'Meet your new fun-pals next week!' 'This won't hurt a bit ...'

Fortunately I was never one of those kids whose parents upped sticks and moved to a grimy new town on the other side of the country, forcing me to win over the bullies in my new class by scoring a hat-trick for the school team, nor abandoned in the countryside with a mysterious grandfather who after dark – along with the other villagers – took root in the vegetable patch and sucked eternal life from the mystical sod (I know that this was a thing because I read about it in the first issue of Misty – the story was called Nightmare: Roots). But I imagine the hollow promises that such kids' parents made to them rang as true as the merry strapline that adorned the front cover of the final issue of many a once-proud title in the great pantheon of IPC/Fleetway comics published in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the twentieth century.

IPC ran a pragmatic policy of 'hatch, match and dispatch' in its comic departments. This meant (according to a 1970s report of the Royal Commission on the Press, quoted in James Chapman's excellent British Comics: A Cultural History) that many of the new comics it launched were done so with the express intention of building a new readership which could then be transferred to one of the company's flagging flagship titles when the shiny new publication was merged into it, sometimes after just a few months. Artist Lew Stringer has said that occasionally 'the top-billing comic was the one with lower sales to the title it was absorbing'. A handful of the cancelled title's strips and characters would make it into the merged publication, sometimes becoming permanent fixtures but more often disappearing after a few months (as did the name of the annexed comic from the title of the 'new' publication, with nary a whimper).

It's worth mentioning that Dez Skinn, who worked for IPC in the early 1970s, describes it as a less cynical operation. On his website he says that 'New weeklies were constantly being launched in (invariably fruitless) attempts to cash in on existing successes. If sales dared to drop below 250,000 a week, they were matched up with an established but ailing title'. Still ruthless, but effective business practice and not as brutal as the suggestion that start-up comics were launched solely to feed the elite.

Those seem to be conflicting accounts of the criteria that governed IPC's new launches and mergers, but it's possible that different decisions were made for different reasons at different times. We are after all considering the operations of a company over three decades. And the merger of comics was not a practice pioneered by Fleetway or IPC nor exclusive to them, as DC Thomson, the other large British comic publisher of the day, also merged several of their titles.

At this point I have to fess up and admit that I had a sneaky liking for the mergers. I know that this isn't what nostalgic comic fans are supposed to say – there is much wailing and gnashing of teeth whenever the hatch, match and dispatch policy is remembered in online forums or histories of British comics. But I have a theory that comic-merger trauma is one of those nostalgic myths – like watching Doctor Who from behind the sofa, or knowing a friend of a friend whose stomach burst open when doing a belly flop off the high diving board at the neighbouring town's swimming pool.

I actually thought it was pretty cool when one of my comics merged with another. It was exciting. An EVENT. There would be a whole new look (a 'new look' was always something to look forward to), and new characters and stories to discover. Even wondering which strips from either of the merging comics wouldn't make it into the new title was more intriguing than upsetting.

Admittedly I was only ever a reader of one of the subjugated comics at the time that it was taken over (Speed into Tiger in November 1980) and twice a reader of the subjugating title (Whizzer and Chips when it gobbled up Krazy in April 1978, and Eagle when it swallowed a Scream! in September 1984 (see helpful comment from Stephen Archer below!)), so I probably got off lightly. I was more often on the side of the all-conquering new masters than the subsumed minors. But there was much cross-advertising in the IPC comics family so we could all keep up with which titles were merging into which. In the period that I was a regular reader there was a total of 14 mergers within the humour, 'boys'' and 'girls'' divisions, and nearly fifty across the 1970s and 1980s. I found it fascinating, and an important part of what made IPC/Fleetway such a rich and vibrant stable of comics.

*

This being the 'fantastic first issue' of this blog, it seems only right that I should bestow a free gift on you my wonderful readers (pals/mates/chums/earthlets). Actually it's been for my own benefit as much as yours that I have created this diagram to chart the publication and merger history of IPC/Fleetway comics in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s (and those that were directly related to them before and after). In all my research as a collector I haven't been able to find a graphic representation anywhere else in any form, so I hope this might be of interest to you. Fun tip: cut it out and pin it on your wall next to your posters of Cheeky, Roy Race and D.R. & Quinch.

You can download a PDF of the wallchart here. Fun tip: cut it out and pin it on your wall next to your posters of Cheeky, Roy Race and D.R. & Quinch.

NB. I researched this chart as well as I was able, but am aware that it may not be complete. Just as I was applying the final touches I learned about a couple of short-lived comics that I hadn't heard of before so the chances are that there are more. If you can tell me about anything I've missed – or got wrong – please do let me know and I'd be delighted to update the chart for a future blog post.

*

So who were the great survivors of hatch, match and dispatch? Many of our favourite characters from the 'lesser' of the two merged comics went on to have long and popular extended lives (presumably with a larger audience) in their new homes. As a reader I was happy to see two of the strips from Speed enjoy lengthy runs in the new Tiger and Speed: Topps on Two Wheels, which followed the escapades of cheeky Evil Knievel-based stuntrider Eddie Topps, and a true IPC classic, Death Wish. The latter told of the tragic adventures of former racing driver Blake Edwards, who wore a grotesque mask to hide the hideous facial disfigurements suffered in a crash, and sought increasingly bizarre challenges of skill and speed in the hope that he might never survive and have to see himself in a mirror again. Death Wish ran for five post-merger years in Tiger and made the cut again when Tiger was merged into Eagle, but the strip was past its best by this stage and didn't last much longer. It had been conceived for a comic that was all about speed, and lost its way a little bit in Tiger, which at the time was supposed to be a sports-themed comic. Eagle didn't really seem to be interested in sport, and at the time of the merger with Tiger it seemed to be mostly action and horror; one would have thought that Death Wish fitted the bill as an 'action' story, but it took a weird supernatural turn with Blake befriending a gang of friendly ghosts, and was soon cancelled.

I'll reveal who I believe to be King or Queen of the Merger Survivors a little further on, but first a few honourable mentions.

Knockout was a short-lived humour comic (June 1971 to June 1973) but it originated a number of characters who went on to become post-merger mainstays of Whizzer and Chips. W&C was the first IPC comic that I read on a weekly basis and by the time I started with it ex-Knockout survivors Fuss Pot, Joker, Pete's Pockets, Beat Your Neighbour and class war tour de force The Toffs and the Toughs were all well-established.

Jack Pott (possibly Fuss's cheerier cousin) was another survivor, living long in the pages of Buster after Jackpot comic had been taken over. He actually had an earlier incarnation in the pages of Cor!! so seems to have been a popular character although I found him a bit dull: his defining characteristic seemed to be that he just won stuff. Faceache was a far greater character, moving from Jet to Buster when they merged in 1971. Drawn predominantly by the brilliant Ken Reid, Faceache had the ability to 'SCRUNGE' his appearance into all manner of gargoylesque visages and he was one of the best characters in Buster until the late 1980s.

Happy-go-lucky Frankie Stein was another great survivor, and not only of the many attempts of his creator/father Professor Cube to lose or kill him. Frankie first appeared in 1960s 'power comic' Wham! then was reanimated for the short-lived Shiver and Shake comic in 1973 and became one of the most popular characters in Whoopee! after those two titles merged. At the same time as appearing in Whoopee!, Frankie helped launch Monster Fun in 1975 and regularly introduced features such as the comic's puzzle page, Frankie's Diary and an occasional one-gag filler strip called Freaky Frankie.

There were fewer merger survivors in so-called boy's comics (I'm using the gender-specific and age-specific categories that IPC was divided into at the time, although the stance of this blog is that all the comics can – and should – be read by all ages and genders). Apart from Death Wish, special mentions go to Strontium Dog and Ro-busters, both of which transferred from Starlord to 2000AD in 1978 and still appear in new stories in the Galaxy's Greatest Comic today, and another of my all-time favourites, Hot-shot Hamish.

Hamish was the trunk-limbed, blonde-locked, Hebridean dunderhead (a sort of Robbie Savage crossed with Desperate Dan) whose cannonball strikes on goal for Scottish footy team Princes Park opposition keepers hiding behind the goalposts. He moved from Scorcher to Tiger when they merged in 1974, and then over to Roy of the Rovers in 1985 after Tiger merged with the less sporty Eagle.

Following much the same career path to Hamish was Billy Dane, star of Billy's Boots. Billy was an untalented schoolboy who came into possession of a pair of old football boots belonging to black-and-white pre-War star Dead-shot Keen. When he wore the boots Billy was magically imbued with Dead-shot's footballing skills and the gift of eternal youth, enabling him to remain a schoolboy for more than 20 years (in Scorcher, Tiger, Eagle and Roy of the Rovers). Either that or Dead-shot's old boots caused to him to keep flunking his 'O' levels.

Mergers were as common among IPC/Fleetway girls' comics as they were in boys' and humour but there were fewer characters or stories that transferred from one title into another. Generally speaking there weren't many ongoing characters in girls' comics, which were more likely to comprise standalone stories and limited-run serials with a beginning, middle and end. This made for more mature and satisfying storytelling – yes, still reasonably formulaic but less so than most of what could be found in boys' and humour comics at least until the early 1980s (I would say that 2000AD – the comic that elected to age at the same rate as its readers – was the only 'boys'' comic that really mastered the art of character and story progression).

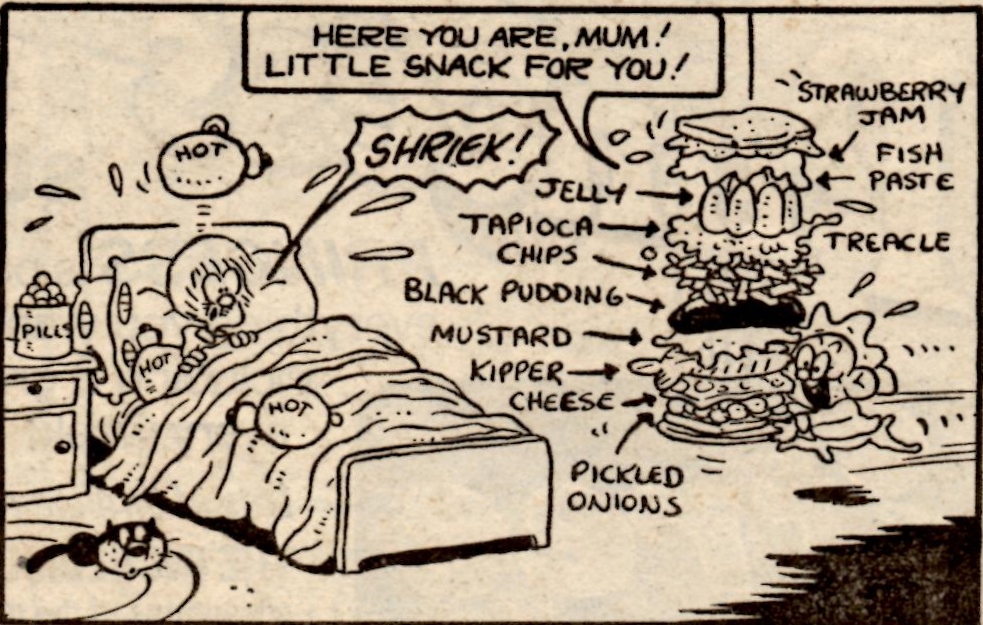

And so to my Number One Great Survivor, chosen not so much for his longevity but for the sheer audacity with which he bounded through one merger after another and made an instant impression in each new home. The irrepressible Sweeny Toddler – created by Leo Baxendale and drawn for most of his run by the equally-brilliant Tom Paterson – was a snaggle-toothed pre-schooler who wreaked chaos for his mum and dad in a wibbly-wobbly world of raspberry blows and slipper wallops.

Sweeny started out in Shiver and Shake, and became the cover star of Whoopee! after his first merger. Whoopee! was eventually taken over by Whizzer and Chips, where Sweeny once again took over the front page, in the process becoming possibly the first character to avoid being categorised as either Whizz-kid or Chip-ite. He made the cut once more when W&C was merged into Buster in late 1990 to become the last humour comic standing. To my mind Sweeny, more than any other character to survive to those twilight days of the IPC comics dynasty, represented the riotous spirit of the very best of its creators.